In Search of Mr. Ripley...

Behind the inspiration for Patricia Highsmith's most famous character

Hello readers and friends,

In the last newsletter I wrote about my inspiration for Where You End, an essay that happened to coincide with a reading binge (and in some cases, rereading) of Patricia Highsmith, including what is arguably her best and best-known novel: The Talented Mr. Ripley. If you’re not familiar with the story, here’s the gist: at the behest of a wealthy New York businessman, drifter-grifter Tom Ripley sets of to “Mongibello,” Italy (based on the Amalfi Coast resort town of Positano) to track down the businessman’s son, Dickie Greenleaf, and bring him back to the States. Ripley inserts himself into Dickie’s life and grows increasingly obsessed with him, an infatuation that continues—and amplifies—after Dickie’s murder, when Ripley successfully assumes Dickey’s identity. Ripley, whose exploits and crimes would feature in four further novels, is a remarkable creation: a psychopath, yet somehow so damn charismatic and pathetic (often in the same scene) that you can’t help but root for him to get away with it all. In Highsmith’s hands, even Ripley’s darkest impulses are relatable, and I wanted to know how she invented him.

By Highsmith’s own admission, she identified with Tom Ripley more than any of her other fictional characters—or alter-egos. In her 1983 handbook Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, she writes, “No book was easier for me to write, and I often had the feeling that Ripley was writing it and I was merely typing.” According to Andrew Wilson, one of Highsmith’s biographers, she even occasionally signed letters “Love from Tom.” The similarities between the famously misanthropic Highsmith and her beloved creation are conspicuous. Both endured miserable childhoods, suffered from low self-esteem, and, in the words of another biographer, Joan Schenkar, were “ruthless—and as ruthlessly attached to the American Dream.”

Highsmith’s inspiration for Tom Ripley wasn’t solely internal. In forming the “germ” for her character, she often cited an experience she had during a 1952 stay in Positano. One morning, standing on the balcony of her hotel, she noticed “a solitary young man in shorts and sandals with a towel flung over his shoulder, making his way along the beach from right to left… There was an air of pensiveness about him, maybe unease. Had he quarreled with someone? What was on his mind?” She never saw the young man again, but in her mind he became the prototype for Tom Ripley, a lonely character whose grand ambitions masked a fear that he would never truly belong. Through Ripley, Highsmith could channel her own long-simmering rage, her own aspirations, her own desire for revenge against everyone who had abandoned, punished, or rejected her.

Highsmith found further inspiration in another source, one that (until this newsletter) has never been fully explored: an article from the New York Herald Tribune headlined: MAN ‘BURIED’ AS FIRE VICTIM SEIZED AS MURDER SUSPECT. Highsmith reportedly clipped the piece and pasted it into her notebook, and The Talented Mr. Ripley was published within the year. This headline intrigued me as much as it did Highsmith, so I dug into the archives to see what more I could find. The tale is as twisted and unsettling as any Highsmith could have dreamed.

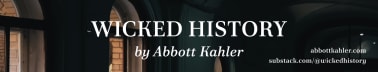

It begins on April 2, 1954, when a St. Louis woman named Betty Anne Paglino contacted the police to report that her husband, Albert, a 28-year-old meat cutter, was missing. He’d left their home “in an angry mood,” she said, after a fight over her refusal to seek medical treatment for her “nervous condition.” Four days later, a fire broke out at a tourist court in the outskirts of the city, causing one fatality in Cabin No. 5. The register revealed that Albert Paglino had checked into the cabin two hours before the fire began. St. Louis police visited Albert’s home to deliver the tragic news to Betty Anne. “Albert was so jolly, so sweet,” she said, and burst into tears. She organized a wake and a burial at Resurrection Cemetery, and everyone agreed—including the coroner—that the death was a tragic accident.

Or so it seemed…

A few hours after the funeral, a woman named Marilyn Patterson was having a drink at a cocktail bar. An old friend of Paglino’s, she was discussing his death with the bartender when she noticed a man walk through the door. She couldn’t believe her eyes: It was Paglino himself, looking very much alive. He stepped inside a telephone booth and closed the door behind him.

“Ed,” Marilyn said to the bartender, “we buried that man this morning.”

“Don’t kid me like that,” Ed said.

Inside the phone booth, Albert made a call to his friend James McCormick, who had been a pallbearer at the funeral.

“Hi, Jim?” he said. “This is Al.”

“Who?” McCormick asked.

“Al Paglino—”

“Don’t kid me.”

“I’m not kidding,” Paglino promised. I’m coming over to see you. I’ve got a story so fantastic I don’t know if anyone will believe me.”

McCormick didn’t truly believe Paglino was alive until he saw him with his own eyes. There was his old friend, standing at the door—a tall and broad, larger than life, always a practical joker. “I thank God to see you alive,” McCormick said, and listened to Paglino’s tale: On the day Betty Anne reported him missing, he’d actually been kidnapped at gunpoint by two soldiers who drove him to Amarillo, Texas. Once there, they kicked him out of the car and he hitchhiked back to St. Louis. McCormick brought Paglino back to his home, where he had a tearful reunion with Betty Anne. Their petty quarrels were forgotten.

News of the miraculous resurrection reached the St. Louis Police Department. Captain Harry Newbold launched an investigation, and learned that Paglino had a good reason for wanting to disappear: outstanding financial obligations to his ex-wife. At the time of the couple’s divorce four years earlier, in 1950, Paglino was ordered to pay $20 per week in alimony—payments he’d failed to make. He tried to obscure his whereabouts by taking a job at a gas station under a pseudonym, Albert Lewis, and opening a bank account under that name. It took four years, but the first Mrs. Paglino eventually found him and took him to Criminal Court, which ruled that he owed her $3600. Paglino received a one-year sentence but was paroled when his father bailed him out. One week after his release, he “died” in Cabin No. 5. Curious timing, Captain Newbold noted, considering Paglino also had recently taken out two life insurance policies worth $5000.

The captain began surveillance on the entire Paglino family, and arrested Albert when he went to visit his father. The suspect repeated his story about being kidnapped, but the contents of Albert’s car—a bloodstained blanket and an empty gasoline can—suggested a darker scenario. A new search through the debris of the cabin fire turned up a wallet filled with photographs, a Social Security card, and other clues pointing to the true identity of the dead man: Willie Burchett, a 33-year-old itinerant railroad worker with a police record that stretched from coast to coast. The captain theorized that Paglino had gotten Burchett drunk, beaten him unconscious, and left him in the cabin to burn to death, hoping that the body would be mistaken for his own. Paglino’s obligations to his ex-wife would be null and void and he could collect his own life insurance. A jury indicted Paglino for first-degree murder, and he was again released on bond. He trial was set for October 18, 1954, but Paglino had other plans.

One month before the trial, on September 14, Betty Anne once again reported her husband missing. After pulling Paglino’s car from the Mississippi River, police spoke to a witness who’d seen a man jump from the car before it hit the water. This time, Paglino’s disappearance seemed permanent; neither law enforcement nor Betty Anne had any leads. When he failed to appear in court on the first day of his trial, his lawyer told the judge that he believed Paglino was dead. The judge had a quick response: “They thought that before.”

One morning early in January 1955, Lois Ford, postmistress of the small town of Calipatria, California, sorted through the mail and noticed a flier from the FBI. She took a closer look: the photograph on the flier bore an eerie resemblance to a man she knew as Frank Beck, who worked as a handyman at the nearby Royal Hotel. She called police, who confronted Paglino at the hotel, showing him the flier. “That’s my picture all right,” Paglino said, “but I don’t remember the name. I don’t remember anything about myself since I left Los Angeles and came here six months ago.” But fingerprints exposed the truth: Frank Beck and Albert Paglino were one in the same.

Life on the run had gone so well for Paglino that he’d married a third time, and his new wife, Annie, was expecting their child. She had no knowledge of his duplicity, or that he was still officially married to his second wife. In the end, neither mattered; she supported him through his trial, held in St. Louis in June 1955. A jury determined that he was guilty of first degree murder for the death of Willie Burchett, and he was sentenced to life in the Missouri State Penitentiary.

The record offers few details about Paglino after the trial. His obituary in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, printed on August 6, 2003, reports that he died, aged 77, at DePaul Hospital in Bridgeton, Missouri. The paper made no mention of any murder or stolen identity or brief stint as Frank Beck. Instead, the obituary claimed that Paglino had worked as a meat cutter for more than thirty years, and had retired in 1999 after five years at Sam’s Wholesale Club—a strange resume for a man who was supposed to die in prison. Which invites several questions: Exactly how long was Paglino incarcerated? Did he secure an early release, and if so, how and when? Did he lie to his boss at Sam’s about where he’d been for the past thirty years? How many people in his life knew the truth, and did he worry that his past might catch up to him? All we know is that Albert Paglino—like Tom Ripley—had managed to finagle yet another new life.

(Sources: St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis Globe Democrat, the Knoxville Journal, the New York Herald Tribune, the New York Daily News)

AND, FINALLY…

The Where You End sweepstakes is still on! Pre-order here for a chance to win a stack of books, a $100 Goldbelly gift card, and this beautifully creepy rabbit mask by Spirit Parade (modeled here by yours truly). Perfect for the spooky season…

If you enjoyed this post, please share with friends or with anyone who might appreciate a bit of wicked history. And, as always, thanks for reading.

Till next time…